COVID-19’s Devastation in Black Communities Began Long Ago

The first three deaths from COVID-19 in Milwaukee county were middle aged black men. Since then, coronavirus has continued to damage black communities at disproportionate rates.

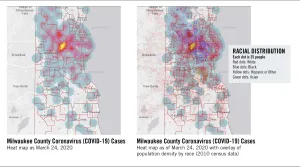

At the time of this writing, in Milwaukee county, black residents made up more than 43 percent of the people who tested positive for COVID-19 and 62 percent of deaths from the disease (WUWM.edu). The black population in Milwaukee county is 27 percent. Check the Milwaukee County Health Department dashboard for up-to-date data.

Current Landscape Meeting Historical Trauma

Across the nation, the mortality rate for black Americans is 3.6 times higher than the rate for white Americans (APM Research Lab Staff). Much can be attributed to community spread in urban areas like Milwaukee, Chicago and Detroit.

In addition, African Americans are more likely to suffer from chronic illnesses like diabetes and high blood pressure and are less likely to have access to health care. Many are essential workers—personal caregivers, sanitation workers and fast food staff—who can’t afford to stay home.

We know that this virus is spreading rapidly and doesn’t discriminate against who can be infected. It’s true the elderly and those with chronic health conditions fall victim, and so do young, otherwise healthy people.

Yet it’s clear there are some identifiable groups who are more vulnerable – when we’re willing to see them and the reasons.

“When certain groups are more vulnerable, we must acknowledge systematic inequities,” says Ann Leinfelder Grove, Wellpoint Care Network’s President and CEO. “when you look back at the history of our country, you can see that, as systems were built, they included structures and rules that created fundamental disadvantages for black Americans.”

Three-Way Intersection: COVID 19, Milwaukee and History

Leinfelder Grove and Wellpoint’s VP of Equity and Human Capital, Kenyatta Sinclair, and VP of Child and Family Well–being, Dwayne Marks, recently gave us insight into the intersections of Milwaukee, equity and COVID-19.

*Responses have been edited for clarity.

Q: For generations, environmental, economic and political factors having been widening gaps between black and white people when it comes to health, education, housing and general wellbeing. When did this start? How far back must we go to get to the root of these disparities?

Dwayne: The answer is slavery. That whole paradigm that allowed one group of people to treat another group of people like this was justified because they (slaves) weren’t even considered human.

Kenyatta: If you don’t see me as a full human being, but as someone who can work around the clock and endure more pain and anguish than you, you are not going to treat me the same.

If you think that I am animal–like, so you run experiments on me to test your theories and medicine, that means you think we are not the same. If I am used as currency; you cannot think I’m a human being.

Q: Historical trauma seems to play a role here. Can you tell us more about historical trauma?

Ann: Historical trauma is the collective emotional harm of a group of people passed down from generation to generation. Slavery, genocide and forced relocation are some examples of mass traumatic events that have affected African Americans, Native Americans and other people of color.

Q: What is life like today for groups who have survived a great deal of historical trauma, given this trauma that was never addressed?

Kenyatta: When you fast forward to today, we see historic events like slavery and genocide have led to implicit bias, structural racism and marginalization for people of color.

Dwayne: Now you have the creation of racist institutions and infrastructures. When you don’t (tackle those systems), you find cities and communities don’t have the help and the advocacy they need. There’s no push for equity.

Where houses are built and who gets loans for them is not equal. It may be true that the number of high school dropouts or incarceration rates are higher for people of color, but you won’t understand why unless you look at these issues starting with that root disparity (unaddressed historical trauma).

Q: Milwaukee has made national news because of its stark inequalities for African Americans. How bad is it?

Ann: Consistently, Milwaukee has been ranked one of the worst places for black people to live, one of the worse places for black home ownership and one of the most segregated cities in the country. Last year, racism was declared a public health crisis.

Q: What else do we know about the impact of racism on COVID-19 and Milwaukee?

Kenyatta: Housing is a huge factor. Look at Sherman Park (nearly one out of every ten positive reported COVID-19 cases are from the neighborhood) and how close the houses are; look at how many people have subpar housing.

Look at the fact that there are no grocery stores, only corner stores and gas stations with no fresh food.

Many people are essential workers, so there’s a higher exposure rate for them contracting the virus and bringing it back to their community. There are some families with multiple generations living in the house, so there’s no room for social distancing.

Q: Why is housing so essential to the wellbeing of Milwaukee neighborhoods?

Ann: In Milwaukee, there have always been high levels of segregation, redlining and gentrification. These all have made for unfair housing. Beginning in the summer of 1967, the NAACP Youth Council, along with Rev. James Groppi, marched for 200 nights for fair housing.

Dwayne: Here’s an example of equal not being equitable. It’s Arkansas in the late 1700s, and black and white communities are segregated. White communities have nicer houses, made of brick and stone, while black communities have houses made of wood and tin. There’s been a lot of tornadoes ripping through the community lately. In this scenario, the town’s version of the health department decided to educate both communities about tornados, so they would know how to protect themselves.

The next day, a tornado hits and dozens upon dozens of black homes are destroyed, and many people die. In the white community, a much smaller amount of the homes are destroyed, and no one dies. The two communities had the same preparation and education. So, what led to more black deaths if they did everything the white community did? It wasn’t, as some might think, a lack of awareness or ambition to seek shelter, it was the housing disparity that led to worse outcomes.

If you look back at the history of people of color in the United States, the disparities in quality of life that still exist today, are not surprising. This pandemic has shined a light on the unaddressed racism that has created gaps in our social, political and economic systems.

So Much Work to Do

“During uncharted times, like the coronavirus health crisis, we are forced to face the discomfort of change and disruption – to our work, school and social lives, for example,” says Leinfelder Grove. “And it’s certainly not comfortable to acknowledge the role of systemic racism in health outcomes but it would be far worse to ignore it.”

At Wellpoint, we try to remedy these barriers through the 5 Pillars of Stability. Research and experience have shown us that children, youth and families need to have stability in five core areas in order to thrive: Health, Education, Housing, Employment and Caring Connections.

We strive to address the impact of trauma, prevent adversity and promote resilience for the people in our care. We take a trauma informed approach to our services that help children and families build life skills, access needed resources and navigate systems of care. To do this work, we must acknowledge systematic racism, historical trauma and the role they play in our collective mental and physical health.

Want to talk? Our therapists are available via telehealth.

Would you like to join us in our mission to facilitate equity, learning, healing and wellness so children and families can survive crisis and go on to thrive? Get Involved.